Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

This article was originally published by The Lawyer’s Daily (www.thelawyersdaily.ca), part of LexisNexis Canada Inc.

Michael Piaseczny and I wrote a two-part series published on December 22, 2020 and January 11, 2021 with an empirical look at child access during COVID-19's first wave under Ribeiro v Wright.

Michael and I would like to thank Prof. Natasha Bakht for her insightful comments and feedback.

COVID-19 hit the legal professional like a punch to the gut. It forced the profession to rapidly change — in many respects, change was needed. But it did not only force the administration of the law to change, it created a tsunami of new legal issues for courts and lawyers alike to navigate. For family law in particular, COVID-19 presented lawyers with waves of separations, divorce applications and child custody issues — anecdotally speaking. (See “Increases in Ontario family law cases: An anecdotal account.”)

In March, Justice Alex Pazaratz of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice offered an early pandemic decision regarding suspension of parenting rights during a pandemic. In Ribeiro v. Wright [2020] O.J. No. 1267, Justice Pazaratz denied authorization of an urgent motion to suspend a father’s access to his 9-year-old son due to the mother’s belief he would not follow COVID-19 protocols — specifically, failing to maintain social distancing. (See also Chrisjohn v. Hillier [2020] O.J. No. 1617.)

We bring narrowly picked preliminary data into the fold and illustrate that family law court battles relating to child custody and access continue to offer predictable and consistent outcomes despite COVID-19’s far-reaching negative impacts. Through focusing on a sample of Ontario court decisions in the first wave of COVID-19, we argue that the court did not alter or set aside a parent’s access to a child as the court has strictly adhered to in Ribeiro v. Wright and places great emphasis on the best interests of the child in that children deserve to see both parents.

Ribeiro v. Wright illustrates how Ontario’s courts will consider access during COVID-19

On March 24, Justice Pazaratz decided Ribeiro v. Wright less than a week after regular operations of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice were suspended due to COVID-19. The court denied the mother’s urgent motion to “suspend all in-person access [to the father] because of COVID-19” (see paras. 4 and 29). The mother did not want the child to leave for any reason and alleged the father would not respect social distancing protocols.

Justice Pazaratz identified the presumption that “all orders should be respected and complied with because “meaningful personal contact with both parents is in the best interest of child” (see para. 7, authors’ emphasis). Justice Pazaratz clearly outlined that children require “love, guidance and support of both parents, now more than ever” (para. 10, emphasis added) and any total ban preventing children from leaving their primary residence — even to visit their other parent — is inconsistent with a comprehensive analysis of the best interests of the child.

Despite this, Justice Pazaratz did discuss that if a parent has a concern that COVID-19 creates an urgent issue, they may initiate an emergency motion. However, it was emphasized that the parent bringing forward the emergency motion should not presume that the mere existence of COVID-19 will result in a suspension of in-person access.

Additionally, Justice Pazaratz set out four factors to be considered on a case-by-case basis:

It is clear that Riberio v. Wright illustrates that Ontario’s courts sought, early on in the pandemic, to protect existing parenting orders and parenting time to children.

The dataset: a sample of the number of cases citing Ribeiro v. Wright

We comprised a dataset of cases which cited Riberio v. Wright during the first wave of COVID-19, which is defined as ending on Sept. 27. Riberio v. Wright was cited within 124 Ontario Superior Court, family court and Court of Justice decisions. Our dataset includes 16 per cent of these cases (20 out of 124 cases). For the complete list of cases used in the dataset, please refer to the authors’ contact information below.

All the dataset’s cases were selected because they cited Riberio v. Wright directly at any paragraph at 7 or 19-24. These paragraphs were chosen to narrow the number of cases within our dataset because they contained Justice Pazaratz’s presumption to respect parenting times and analysis surrounding COVID-19 and parenting issues. Three variables were operationalized:

Another parent’s access was more likely to be expanded or not impeded by COVID-19

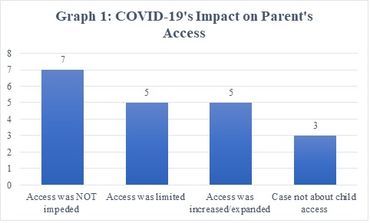

Through analysis of the dataset’s selected cases, it became apparent that the other parent’s (non-moving party) access was more likely to be improved rather than impeded by COVID-19. Graph 1 illustrates that, in most cases, COVID-19 failed to impede the other parent’s access to the child. In contrast, a child’s access was limited due to COVID-19 in only five instances.

An immunocompromised justification produced mixed results for limiting access. For example, an immunocompromised parent failed to reduce the other parent’s parenting time. (See Sereacki v. Berdichevsky [2020] O.J. No. 1867, para. 10 and Little v. Cooper [2020] O.J. No. 1424, para. 10). However, an immunocompromised child did result in temporary limited access (see E.M.B. v. M.F.B. [2020] O.J. No. 2344, para. 10).

An unanticipated result was that COVID-19 led to an increase, or expansion, of the other parent’s access. For example, in A.A. v. R.R. [2020] O.J. No. 1671, the court expanded the father’s access to alternating weeks because their parenting time centred around the child’s school routine which was impacted by COVID-19.

In part one of this series, from our new dataset, we found that in most cases, COVID-19 was more likely to increase or not impede a child’s access compared to limiting it.

It is clear from our succinct analysis that the treatment of precedent has been upheld during an unprecedented time, specifically the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, our analysis shows that the court continued to use the “best interests of the child” lens to maintain child custody and access, despite pandemic concerns.

Since the penning of Justice Alex Pazaratz’s words in Ribeiro v. Wright [2020] O.J. No. 1267, Ontario courts have cited it 124 times within the premier’s self-described “first wave” of COVID-19, from mid-March until Sept. 27, 2020. Given the dramatic changes in the legal profession since the start of the pandemic, we used s. 20 of the Child Law Reform Act as a backdrop to examine how courts have subsequently treated Justice Pazaratz’s decision in Ribeiro v. Wright in child custody and access cases.

Moving party’s relationship to child relatively equal compared to most children

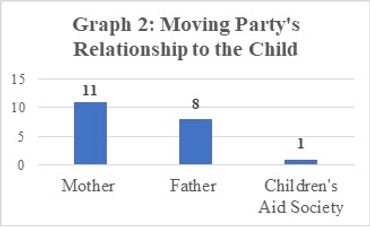

Graph 2 illustrates the different parties who brought forward a motion for child access. The number of cases between each party was relatively balanced, but a child’s biological mother was slightly more likely to bring forward a motion related to access compared to a biological father. We do emphasize that this article does not examine the moving party’s role within a custody arrangement.

Dataset: Main reasons for bringing forward a motion

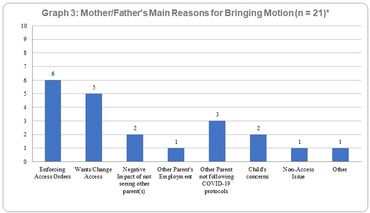

Graph 3 illustrates the different reasons that parents brought forward their motions. The moving party predominantly brought forward motions to enforce an existing access order or change to the current access order. Over half of the cases fall into the “Enforce access orders” and “Wants/change access” categories.

Another popular reason was the “other parent is not following COVID-19 protocols,” with the number of cases at three, but the moving party’s success rate among these cases is mixed (see Little v. Cooper [2020] O.J. No. 1424, J.F. v. L.K. [2020] O.J. No. 4043 and Guerin v. Guerin [2020] O.J. No. 1396).

Conclusion

This article offers introductory empirical insight — during a time of epidemiological crisis — into the study of family law, specifically child custody and access, because this area of law, like others, has been greatly affected in many facets.

Even before COVID-19, those in the area of family law have argued that the practice area needs more empirical insights so family law can become “more inclusive and move beyond narrow dominant norms” (see Clare Huntington, “The Empirical Turn in Family Law” (2018), 118:1 Columbia Law Review, 227 at 231).

The premise behind this argument is that greater empirical study of family law has the ability to “give decisionmakers a clearer sense of areas in which legal inputs might yield particular social outcomes … [and that] it holds the potential to help depoliticize battles” by attempting to separate social beliefs from political arguments (see Huntington).

This short piece is a mere introductory step into analyzing empirical observations of family law during COVID-19. It is thus key to note that this article presents a piece of a larger project and does not make any causal assumptions.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.